Speed Racer, meet Pinball Wizard!

It has been said by many that humans are lousy at assessing risk, certainly in an informal, heat of the moment setting. An easy example could be Jordan’s Furniture, a Boston-area institution for decades, more recently known for offering complete refunds on furniture bought early in the year, if the Red Sox win the World Series. The first year they offered the promotion, 2007, that’s exactly what happened. There was much dancing in the streets around Friendly Fenway, and about 30,000 people got free furniture, on top of seeing another duck boat parade.

And yet, this was a most incorrect example — first off, Jordan’s Furniture was insured for exactly that scenario (yes, you can insure almost anything!) so their exposure to significant loss was capped. (No-one has come up with an exact figure, but I recall it was rumored to be around $1 million.) Second, their insurer ran the numbers very carefully before underwriting that bet. Asked in an interview if they would write that policy again, theirs was an emphatic yes: it was a carefully calculated risk, and it just so happened that lightning did indeed strike in Fenway. As it turned out, that insurer wrote many policies that year that landed squarely on the correct side of the ledger. They won far more many bets than they lost. Jordan’s was only the very visible example of a bet gone wrong — to the tune of about $60 million. That’s the cost of doing business in the big leagues.

Insurance is one of the most sober practices of risk assessment. Actuaries crunch reams of data drawn from every angle imaginable before they make a move. In the above example, the 86 year long drought of the Red Sox was considered. The team had won in 2004, and many of the same players were still on the roster. But they also no-doubt looked at the state of the rest of the American League, to get a sense of whether Boston would even get a wildcard berth come autumn. Then to the National League, to assess likely contenders in the big game. And then everything else — age and health of players, and of course, who plays whom on the upcoming schedule. Pro sports are nothing if not a gigantic pile of statistical information, so they had a lot to go on, and I’m sure the insurers felt pretty confident in their assessment that things would go their way. Happily for the Fenway Faithful, the insurers lost.

But what about the rest of us, the mere mortals?

Humans in their daily existence need to assess risk in a much more fluid forum, and daily life rarely offers even a fraction of the data you can find in pro sports. If I step outside now, what’s the chance I’ll get hit by an engine falling off a jet plane flying overhead? Almost non-existent. If I hike across Katahdin’s Knife Edge on a humid summer day, what’s the chance I’ll get caught in a pop-up thunderstorm? Well, it’s not an every day occurrence, but it’s a significant enough risk that the park has plentiful warnings posted all over the place. Cross the street about 100 feet in front of a truck that’s moving at 30 miles an hour? I’d probably get away with it, but if I were to stumble, it’s gonna hurt. But there’s not much data you can crunch to figure out those risks in the moment. You need to rely on matching up patterns that you see, hear, experience, and oftentimes, just hope for the best.

One of the impediments to accurate risk assessment in a fluid environment is pattern matching. We do this all the time, and not just to assess risk. We see a particular set of things happen, and that tells us to expect something in particular. Anyone who watches football knows when the teams line up in a certain way, a small set of outcomes is very likely to happen — maybe the offense is going with a passing play, or the defense is going to blitz, or whatever. In a theatre, you know when the house lights dim, the audience will quiet down, and the curtain will open a moment later. Read a book, and you know the first chapter typically introduces the main characters. The second to last usually winds up the action, while the final chapter wraps up the story. White movie posters usually mean it’s a comedy. Black, blue, and yellow ones usually mean it’s an action flick.

There is always a fly in the ointment…

Unfortunately, not all of life is this neatly packaged. Many times, people have to assess risk based on incomplete information. You head to the mountains, and although you’ve read the Higher Summits Forecast, you also know that much of that is really specific to the summits over 5,000 feet, usually bald, and the closer to Mt Washington, the better. I can recall a day spent on the Kinsmans: the forecast called for clearing skies by lunchtime, and yet, I was inside the pingpong ball all day. I’d thought they pooched the forecast, but in reality, it was just the fact that Kinsman Ridge was running interference against all the clouds that came in from the west. Just my luck. Anyone who’s hiked North Twin a couple times knows that it’s not a great choice after mid-springtime, especially after a heavy rain, unless you’re approaching from South Twin.

Compounding that is the emotional component. It’s easy to let less rational elements cloud our thinking. Some of this is more excusable on some levels. Your boss had some strong words with you yesterday? That’s going to make you want to be in the office bright and early today. You spent the last five hours slogging through muck and mud? You’re so far along, and just a little bit more will get you to the summit. Maybe it’s a perfect day and you don’t want to waste an opportunity just because something doesn’t seem entirely right. Or perhaps everyone else is moving forward, so “it’s just me… I should trust that my companions aren’t wrong.”

Road or Rink?

Today, I had planned to go hiking. As things turned out, unexpected road conditions conspired to make that a dream instead of reality. Instead, I got to see examples of poor risk assessment laid out all over the roadways for what few miles I did travel this morning. In the early hours, some rain fell, and that made a really persnickety glaze all over everything. I was hoping that once I hit the major roadways, that things would have broken free. This was a heck of a storm that defied the usual sanding. I drive tens of thousands of miles every year, and am usually very confident behind the wheel, but this got even my nerves up. This storm will be a boon to body shops everywhere, and in a few cases, people are in need of a new ride outright, having played bumper cars with other motorists and various other stationary objects.

One thing I did notice was that most truck drivers had their rigs pulled off the side of the road, waiting for the mess to subside. The guys who clock countless miles each year knew the best course of action was inaction. It would be some time until they could safely head to their destination, but that was preferable to getting into a wreck and not reaching their destination at all. It highlights a failing of pattern matching: you can only match patterns you’ve seen before. We gripe about “those idiots who don’t know how to drive”, and there’s something to that. If you’ve lived around here long enough, you should know that snow and ice are as slippery as greased lightning. But young people haven’t had the time behind the wheel to get enough of a sense of what that really means. If the bad weather comes on the weekends, and you’re not driving much then, you’re not going to have experience making that decision.

Who do you trust? Yourself? Is that really a smart idea?

As a side note, I could also gripe about car companies and their adverts, touting their unbelievable traction control. Or tyre companies that promise better grip than a gecko. The erroneous trust and belief that four wheel drive will get you out of anything. But that underscores the fallibility of human judgement — we happily assume that our car has our backs, when it’s still the loose nut behind the wheel making the decision to turn the key in the first place.

But that side note has another side. Your risk of dying in a plane crash is pretty remote — about 1 in 2 million. Your risk of being killed in a car crash? About 1 in 8 thousand. You’re way more likely to die in a car than a commercial plane. And yet, it’s a very common refrain: people drive because they’re afraid they’ll die in a plane crash. Thank the media. Car crashes are so common that they almost never make the evening news, and afterward, there’s even less of a chance that there will be a follow-up. An airplane gets a flat tyre as it backs away from the terminal? That’s front page, above the fold before they can swap out that tyre, and weeks later, there’s a special news team still hard at work filing stories about it. So not only are we starving for examples of good and bad outcomes, our perception is skewed. We are really crummy at making real assessments of risk in the moment.

What’s the logical choice?

I probably got about five miles down the road before pulling the plug. Thankfully, I got back home safe, and my car is none the worse for wear. Turning to the news, it’s not just cars playing pinball on the streets, but even pedestrians on the sidewalks are having a tough time. So this was a heck of a storm by almost any metric. I think it was a smart idea to turn around and call it a day. The mountains will still be there next time. At least as I write this, I should be, too.

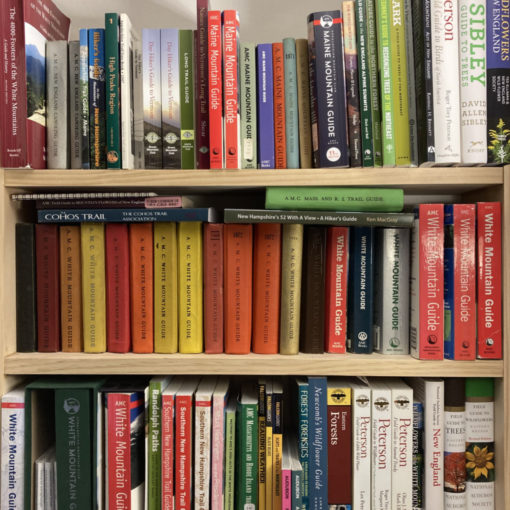

I just got my most recent copy of Appalachia, and inside was the usual dissection of accidents in the mountains. One thing I noted was an avalanche that killed an experienced backcountry skier, who was going down part of the Ammonusuc Ravine trail. That’s going into my risk assessment now, especially because that’s one of my preferred routes up Washington. For anyone who doesn’t get Appalachia (see the AMC’s website for details) or any of the other recreational journals that dissect accidents (this could be aircraft pilots, scuba divers, and many others) I highly recommend reading them and improving your ability to assess risk.

Stay safe out there.